Happiness is a tricky to pin down as a concept. It depends so much on who’s measuring and why.

It used to be rounding an end-game boss in World of Warcraft.

|

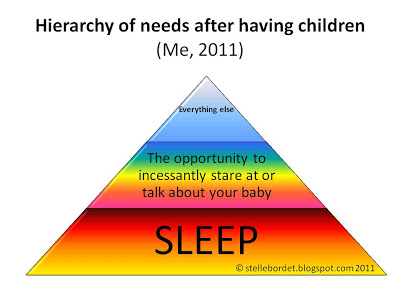

| Late nights… Not what they used to be. |

|

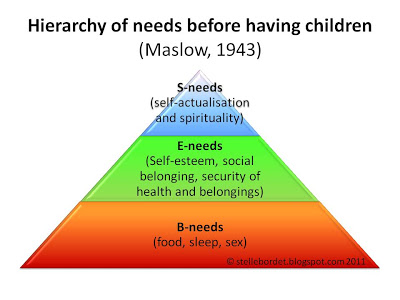

| Maslow’s original hierarchy of need, reproduced lovingly in MS Word ca. 2012 |

I remember reading a study which said that parents actually report higher levels of overall, or what I would deem existential, happiness.

However, when measured in a diary-style throughout the day, they report more moments of low levels of happiness than do childless people.

This makes sense. Again, the hierarchy of needs being bombed to bits. Changing diapers when you need to pee, eat and sleep and are denied either of these, is not actually fun.

They argue quite persuasively that the paradox rests in part on three solutions provided by evolutionary psychology.

First of all, having children does, as noted by the mother quoted in Dagbladet, does play havoc with your ability to satisfy your lower level needs.

You don’t sleep, you eat more Grandiosa than you thought possible and you hardly ever get to have sex for more than 4 minutes at a time.

Secondly, «the modern-day context of raising children is at odds with our ancestors’ environments» (p. 330). It takes a village to raise a child, and that child should then move out to make their own ends meet when they hit teenage years.

Unfortunately, these days, single parents often raise children with little familal support, and the kids stay on to torment their parents long into their 30s. Single parents are the most miserable, and probably for that very reason. It takes more energy than one person can reasonably muster without feeling exhausted rather frequently.

However, the long-term benefits of having children, i.e. being looked after in old age and seeing them grow into independent individuals as your living legacy, has evolutionarily speaking been worth it, as expressed by the old ladies in the Dagbladet article. So we do it even though it makes us uncomfortable, tired, fat and sex deprived in the short run.

One of Bøllemammas commenters, Bondekona, claimed that she has experienced a greater range of emotions since having children. Lyubomirsky and Boehm argue that experiencing a wide range of emotions in itself gives satisfaction, despite some of those feelings having a negative valor, quoting Tennyson’s «tis better to have loved and lost, than never to have loved at all».

They add that happiness and satisfaction research might simply fail to take this into account and is therefore left unable to capture what is wonderful about parenthood due to method and measurement problems.

I’m not sure if I agree with this last point though. The thing about emotion is that like physical pain, it is almost impossible to remember properly.

When you were 12 years old and your first boyfriend asked you out and then kissed you, you really genuinely thought you would explode with joy. When he dumped you two weeks later, you really, genuinely thought you were going to die. For ever. And never love or be loved again.

It is easy to belittle these teenage feelings, enhanced as they are by an unmyelinated prefrontal cortex. But that doesn’t make them less real. I’m not sure that my hormone-laden ecstatic first weeks with Bolle were actually more intense. It’s just that the contrast to my regular, everyday range of adult-controlled emotion is larger.

What also makes a difference emotionally speaking, is the heavy burden of responsibility which comes with parenthood. When you feel joy in parenthood, that you’re doing it right, that your beloved bundle of joy is smiling and satisfied and happy, you also feel a deep sense of relief that this is so.

And because I would argue that, in almost every culture, parenthood is seen as the greatest responsibility an individual or family may take on, the relief that you are shouldering this responsibility, and the sense of coping and mastery when your child thrives, is also the greatest you will experience.

So, for me personally, has parenthood made me happier? Well. I do like sleeping. And eating. But I also really enjoy learning new things every day. And being a parent, I get to know a little more about Bolle every day. It’s like never having to leave her presence to find satisfaction. And actually still manage to cook from scratch most days.

Apart from today, when I ran across a busy road to get a kebab dinner for the family. Then I dropped my phone and it was run over by a car and crushed.

But seriously, I do think I’m happier now than I’ve ever been.